A clincher sentence is a concluding sentence reinforcing your key message.

This article discusses how to write a clincher:

It happens to me surprisingly often.

I’m half skimming, half reading a fairly interesting article—all the way until the last word.

But as soon as I’ve finished, I’ve already forgotten what I’ve read.

If you want readers to remember your words, you need to invigorate your message and jump-start your readers into action.

And the easiest way to do that?

Write a clincher sentence.

A clincher sentence is a concluding sentence reinforcing your key message.

You’ll find clinchers as the last sentence of a well-written blog post, essay, or book chapter; or at the end of a section in a blog post—before a subhead introduces the next section.

A clincher sentence is a soundbite, communicating a nugget of wisdom. It’s a memorable point that may linger in your reader’s mind long after she’s finished reading your content.

Want to know how to write these powerful sentences?

In his memoir My Father, the Pornographer, Chris Offutt ends most chapters with excellent clincher sentences.

For instance, the ending of the 4th chapter gives us insight in the son’s relationship with his father:

(…) I realized the landscape would always hold me tight, that I could never escape, that in fact what I loved and felt most loyal to were the wooded hills, and not my father.

And the 25th chapter ends as follows (note: cons refers to conventions where his father’s fans would gather):

Dad seldom left the house over which he held utter dominion. When he did leave, he went to cons, an environment that assuaged his ego in every way. He grew accustomed to these two extremes and became resentful when his family failed to treat him like fans did. We disappointed him with our need for a father.

Ouch. We disappointed him with our need for a father. A hard truth.

If writing was a boxing match, the clincher sentence would be the knockout blow.

But how do you deliver a killer punch?

To write a clincher sentence, you first must know your key message.

So, think about this: If readers would remember one thing from your article or book chapter, what would it be?

If you can’t think of the key message, your idea might still be a little fuzzy. Let it simmer for a while, and then revisit your post. Which question do you want to answer? What problem do you help solve? What is your key tip?

To get unstuck, use one of these sentence starters to help formulate your key point:

In educational or inspirational writing, you can use the two-punch approach. Firstly, remind readers what you’ve explained already. And secondly, nudge them to implement your advice.

For instance, Mark Manson uses this approach in his article about the most important question of your life. His penultimate sentence summarizes his key point:

This is the most simple and basic component of life: our struggles determine our successes.

And his last sentence addresses the reader directly to nudge him to implement his advice:

So choose your struggles wisely, my friend.

At the end of their book Made to Stick, Chip and Dan Heath take the same approach. The penultimate sentence summarizes their key point:

Stories have the amazing dual power to simulate and to inspire.

And their very last sentence encourages readers to implement their advice by telling them it’s not as hard as they might think:

And most of the time we don’t even have to use much creativity to harness these powers—we just need to be ready to spot the good ones that life generates every day.

Remember, your clincher sentence is the killer punch encouraging readers to implement your advice.

So, summarize and inspire.

(See what I just did? That was another two-puncher.)

My favorite type of clincher sentence sketches a vivid image, giving energy to your key idea.

Chris Offutt ends the 5th chapter of his memoir with a vivid story—the clincher sentence is the last sentence (I made it bold):

A week after the memorial service [of my father], I took Mom to a greenhouse built of plastic sheeting. Mom selected a plant with white flowers, then smiled, shook her head, and chose red flowers instead.

“Your father was color-blind,” she said. “I only bought white flowers so he could see them.”

She took the red ones home. After fifty years Mom planted flowers she liked in her own backyard.

And Mark Manson sketches a vivid image at the end of his post about the real value of money—the clincher sentence is in bold:

The real value of money begins when we look beyond it and see ourselves as better, as more valuable, than it is. When it’s not about the accumulation of stuff but rather the enactment of experiences. When it’s not about the mug but rather the coffee that’s in it.

Vivid images haunt readers, popping up in their minds hours—or even days—after reading your content.

At the end of a book or blog post, you don’t have a choice. To avoid your writing petering out, finish with a clincher sentence.

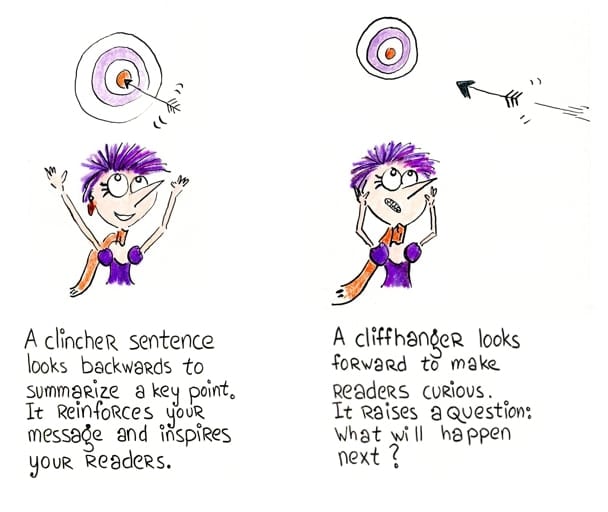

However, at the end of a book chapter or blog post section, you can choose. You can either look ahead and make readers curious to read on, or you can look back and summarize your key message.

To look ahead, use a cliffhanger to raise a question and make readers lean forward, eager to learn more. For instance, in the gripping book American Kingpin, Nick Bilton uses cliffhangers at the end of each chapter.

Here’s the last sentence of the first chapter:

“You got a minute?” he said as he threw the white envelope on the desk. “I have something important I need to show you.”

And the end of the second chapter:

And yet, as he hopped into the car next to his sister, he also didn’t know that in just five years he would be making that amount of money in a single day.

And the end of the 3rd chapter:

But what wasn’t clear to either of them, as they rolled around on his dinky bed in the basement, was that the relationship they were about to embark on would be the most tumultuous romance of Ross’s and Julia’s adult lives. And, for Ross, it would be his last.

Before I started reading the book American Kingpin, I already knew the outcome. I knew Ross Ulbricht gets jailed. Yet, the narrative is so gripping and the cliffhangers so compelling, that I couldn’t put the book down. I wanted to know exactly how the story unfolded.

You don’t have to choose between a clincher and a cliffhanger.

You can use them both.

For instance, in their book Decisive, Chip and Dan Heath explain how to make better choices in life and work. The closing paragraph of the introduction starts like this:

We may make only a handful of conscious, considered choices every day. But while these decisions don’t occupy much of our time, they have a disproportionate influence on our lives.

Then comes the clincher sentence with a vivid image:

The psychologist Roy Baumeister draws an analogy to driving—in our cars, we may spend 95% of our time going straight, but it’s the turns that determine where we end up.

And they end their introduction with a cliffhanger, making us curious to read on (what’s the four-part process?):

This is a book about those turns. In the chapters to come, we’ll show you how a four-part process can boost your chances of getting where you want to go.

So, at the end of a section or book chapter, you have 3 options:

And, of course, each sentence can keep a reader engaged or turn him off.

Yet, your clincher sentence is more important than other sentences.

Because it’s the clincher that reinforces your message.

So, write a strong sentence.

The Enchanting Blog Writing course (rated 4.9 out of 5.0) teaches you how to captivate, educate, and inspire your readers.

“Each video lesson is under 10 minutes. I could learn in tiny increments and go at my own pace, whether it’s one module a day or one lesson a day. Every step felt doable and I could apply what I learned and see how it made my writing better. I was able to add one or two new elements to my writing every week without feeling overwhelmed.”